Critical Annotation/Dossier

This dossier engages contemporary feminist and materialist frameworks to interrogate the entanglement of beauty, ornament and narrative within expanded painting practice. Across the posts, I have examined how artists deploy material excess, language and ornamentation to destabilise gendered hierarchies within visual culture. Theoretical influences span from Griselda Pollock’s Vision and Difference and Susan Sontag’s An Argument About Beauty to Maria Elena Buszek’s Extra/Ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art and Oleg Grabar’s The Mediation of Ornament. Collectively, these texts articulate a feminist material discourse that positions ornament as a site of meaning production rather than just supplemental or decorative.

My approach draws particularly on feminist material practice and new materialist thought. The works of Ebony G. Patterson, Kate Just, and Ruth O’Leary foreground the politics of “feminine” labour (beading, knitting and stitching) as both language and critique. Through these precedents I align my own practice, which similarly employs embellishment and decorative process, with an expanded understanding of craft as a critical methodology. Budzek’s writing provides a theoretical grounding for this position: the decorative is not an aesthetic retreat but a political strategy that revalues care, repetition and embodied making.

A secondary framework emerges through semiotics and communication design, explored via the text-based practices of Kate Just, Barbara Kruger, Ruth O’Leary and Jenny Holzer. These artists demonstrate how typography, script and slogan function as material gestures that collapse distinctions between design, craft and fine art. My background in communication design informs this reading: I view typographic form as a carrier of ideology, where visual language such as flourish, repetition and ornament can shape the reception of meaning as much as the content. Holzer’s use of cursive script and Just’s knitted typography both exemplify how aesthetics of legibility and labour produce tension between softness and authority.

Across the dossier, the unifying theme is the recuperation of beauty and ornament as critical tools. From Ella Walker’s narrative frescoes to Jess Johnson’s textile cosmologies, each precedent demonstrates that decoration can be speculative, subversive and resistant. This through-line reveals a constant methodological logic: to analyse how surface operates as a theoretical space. My engagement with Grabar’s notion of ornament as an “intermediary” provides a historical counterpoint, situating contemporary practices within longer material genealogies of vegetal and geometric patterning.

The artists and theorists discussed form a community of feminist and post-disciplinary practitioners who bridge fine art, design, narrative and craft. By reading these works together, I construct a lineage that legitimises my own studio approach, where embroidery, beading and decoration become means of thinking through the politics of perception. The dossier functions both as analysis and as positioning statement, mapping where my practice sits within current debates on materiality, affect, and the visual politics of gender.

Ultimately, this critical framework allows me to recognise my work as part of a broader theoretical discourse which treats surface as a generative field existing between thought, labour and beauty.

Maria Elena Buszek - Extra/Ordinary Craft and Contemporary Art (2011)

For my last blog post, I wanted to circle back to something recommended to me after the first assessment: Maria Elena Buszek’s Extra/Ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art. The two chapters that have really stuck with me are Dennis Stevens’ “Validity Is in the Eye of the Beholder” and Louise Mazanti’s “Super-Objects: Craft as an Aesthetic Position.”

Stevens’ essay reframes craft as a set of overlapping communities of practice rather than static fields, each defined by its own materials, vocabularies, and internal systems of validation. He describes how these communities form through “shared sensibilities, artifacts, vocabularies, and styles,” and how younger generations of makers (especially within DIY and digital craft movements) are challenging twentieth-century hierarchies of legitimacy. I see my own practice sitting within this shifting terrain: not quite within traditional studio craft, but definitely within a post-digital, feminist network that values care, repetition, and ornament as intellectual labour.

Mazanti’s concept of the super-object expands this further. She argues that craft objects occupy a semi-autonomous space between art and design: what she calls a “super-object,” which draws meaning both from material culture and aesthetic contemplation. This framework is useful for understanding my own stitched, beaded, and embellished works, which function both as tactile artifacts and as vehicles for narrative and critique.

Together, these essays have helped me see craft as a discursive system rather than a medium: a site where communities negotiate value, identity, and belonging. My practice participates in this expanded field of craft that Mazanti and Stevens describe, one that collapses boundaries between art, design, and lived experience.

In many ways, this book has been the theoretical anchor beneath the semester’s experiments. It clarified why I’m drawn to embellishment and surface (not as escapism, but as an argument about meaning-making itself). Within Buszek’s framework, beauty and labour become sites of resistance, and ornament becomes both method and message.

The Mediation of Ornament - Oleg Grabar (1992)

Oh, I almost forgot about this book I read right back at the start of semester, Oleg Grabar’s The Mediation of Ornament (1992). I was fascinated by how Grabar refuses to treat ornament as mere embellishment. He describes it as an intermediary, something that mediates between viewer and object, between surface and meaning. In his words, ornament isn’t a distraction from the “real” work; it is the work’s way of thinking.

He writes about vegetal motifs appearing through art and architecture across cultures, and how these forms always suggest life, motion, and transformation. They’re not static decoration but living systems of growth and a visual coded language that is universally recognised. I love the idea that ornament isn’t passive, but that it moves and animates.

Looking back, I can see how that thought has threaded through everything I’ve done this semester. When I bead, embroider, or paint, I’m not “just” decorating, I’m building a surface that breathes and that draws the eye in and then beyond itself. Grabar describes ornament as a kind of demon, a mediator that transforms whatever it touches, which feels true to my own practice. The more I’ve leaned into embellishment, the more I’ve realised it’s not an excess, it’s a form of thinking.

Jenny Holzer - Action Causes More Trouble Than Thought (2021)

Jenny Holzer - Action Causes More Trouble Than Thought (2021)

This work is such a wonderful look at how communication design principles can impact the reading of a work. Instead of stark, authoritative type (which would seem to fit the message being presented), Holzer uses elegant cursive: looping, ornamental script that carries all the baggage of handwriting, domestic craft, and sentimentality. The phrase itself sounds like a warning, but written this way, it feels intimate- almost tender. The message contradicts its own delivery: trouble rendered beautifully.

I find this fascinating through the lens of typography. Coming from a communication design background, I’ve been trained to think about how letterforms communicate beyond language and how a font’s rhythm and historical context shape meaning. Holzer understands this. She weaponises prettiness. The script feels feminine, polite, decorative, yet the content is sharp, reflective, and vaguely menacing. It’s the tension between flourish and authority that gives it power.

It makes me think of Kate Just’s knitted text works, where the softness of the medium complicates the directness of the message. Both artists use material and form to distort expectation, Just through slowness and tactility, Holzer through aesthetic contradiction.

For my own practice, this opens a new way of thinking about ornament. If typography itself can be a site of friction and can hold resistance, then perhaps decoration isn’t a distraction from meaning, but a vehicle for critical appraisal and analysis. Holzer’s script invites us to read beauty and danger in the same line.

Thinking about both artists makes me reconsider how text might operate in my own work. I often rely on visual rhythm and ornament to communicate feeling, but typography carries its own weight. It has the capacity to be both design and art and reveals its politics in the space between what’s said and how it’s made/presented.

Jess Johnson - Various Works (2024)

Jess Johnson and Cynthia Johnson - The Tower of Babel (2024)

Jess Johnson’s recent textile works Necrotic Scroll (2024), Tower of Babel (2024), and We Can’t Keep Going the Way We’ve Been Going but We Know No Other Way to Go (2024) mark a fascinating turn in her practice. Known for her complex worlds built through drawing and virtual reality, Johnson has translated that language into quilts and fabric banners, pulling her speculative cosmologies into the realm of touch.

I’m very interested in how she uses textile traditions like quilting to materialise systems of belief. Tower of Babel in particular feels like a collision of myth and material: ancient narrative reimagined through cloth, colour, and repetition. There’s something devotional about these pieces which I attribute to my own valuation of labour and craft; particularly those which are considered traditionally feminine or domestic (and subsequently denigrated from the world of contemporary fine art).

Jess Johnson and Cynthia Johnson - Necrotic Scroll (2024)

This move into textile feels political too. Quilts and banners have long been associated with collective labour, protest, and storytelling: from suffragette banners to community quilts. By bringing her otherworldly architectures into this format, Johnson connects speculative fiction to a lineage of feminist and communal making, and practically realises this by co-creating some of these artworks with Cynthia Johnson.

I’m drawn to how this resonates with my own work. They can carry cosmologies, grief, protest and devotion. Johnson’s quilts and banners feel like portals, but also warnings; tactile, beautiful reminders that belief systems, like fabrics, are always being stitched, unpicked, and remade.

Jess Johnson - we can’t keep going the way we’ve been going but we know no other way to go (2024)

Griselda Pollock - Vision and Difference: Feminism, Femininity and Histories of Art (2012)

I didn’t expect a page of photos to feel so poignant, but Griselda Pollock’s chapter “A Photo-Essay: Signs of Femininity” does. She places Rossetti’s portraits of Elizabeth Siddal and Jane Morris next to cosmetics ads and film stills of Garbo and Dietrich and suddenly it’s obvious: the same face keeps repeating. The same soft mouth, tilted head, distant gaze. Different mediums, same script.

Pollock argues that “femininity” isn’t something women possess, it’s something that’s made, carefully produced by images, sustained by repetition. Once you see it, you can’t unsee it. The Pre-Raphaelite muse becomes the movie star becomes the influencer. The ideal just changes costume.

What I like about this essay is how it messes with the idea of beauty as timeless. It’s not eternal, it’s historical, very coded, and taught. And that makes it possible to rewrite. It makes me think about my own work, and all the “feminine” materials I use, not as clichés but as tools. If beauty is constructed, it can also be reconstructed.

Maybe that’s the work I want to be doing: building new signs of femininity that don’t serve the gaze, but speak back to it.

bell hooks: Art On My Mind (1995)

This week I’ve been reading bell hooks’ Art on My Mind: Visual Politics, which explores how art shapes the way we see ourselves and the world around us. Hooks argues that representation is never neutral and that “the function of art is to do more than tell it like it is; it’s to imagine what is possible.” I love this idea that art can open up new ways of being, not just mirror existing ones.

I really enjoy her insistence that emotion and politics belong together. Hooks resists the idea that critical art must be detached or purely intellectual. Instead, she treats feeling as a legitimate way of knowing. That feels close to my own practice, where I work through ideas using codes of beauty, sentiment, and ornament. I’ve sometimes worried that my focus on whimsy or prettiness makes my work seem less serious, but hooks reframes that and posits that softness and emotion can be radical when they push against systems that reward detachment or cynicism.

Her writing also makes me think about visibility: who gets represented and whose images are valued. Hooks calls for art that makes space for new subjectivities, for ways of seeing that are compassionate and complex. It’s a reminder that art doesn’t have to be loud to be political but it can also be tender, reflective, and rooted in care.

Wangechi Mutu - Yo Mama (2003)

Wangechi Mutu’s Yo Mama (2003) is a collage that features a reclining female figure, assembled from fragments of glossy magazines and medical imagery. She is pierced through the abdomen by a snake-like spear. The work draws on biblical imagery, in particular the story of the fall from grace in Christianity.

Mutu’s practice often centers on the female body as a contested site, using collage to expose how race, gender, and sexuality are constructed in visual culture. In Yo Mama, she plays with tropes of the femme fatale and the serpent from Biblical myth, but reconfigures them through a lens of Afrofuturist hybridity. The result is an image that is both beautiful and grotesque but invites further consideration (reminding me of Ebony G. Patterson’s works!)

This doubleness reminds me of Susan Sontag’s writing on beauty’s contradictions: how it can never be neutral, always bound up with power. Mutu’s figure is hyper-beautiful, but also split apart, weaponised, stitched from fragments. The work also speaks to material histories: collage as a medium of rupture and fragmentation which feels relevant to how I use mixed media.

For my practice, Yo Mama offers a model of how ornament and violence can coexist, how seductive imagery can be the very surface that unsettles. It pushes me to think about how my own use of whimsy might similarly carry unease, and how material excess can be political rather than decorative. It makes me ask - how can I utilise dissonance, created by beauty?

Ruth O’Leary - Feeling Drawing Thinking (2024)

Ruth O’Leary - Feeling Drawing Thinking - 2024

Ruth O’Leary’s Feeling Drawing Thinking positions drawing as a direct channel between thought and sensation. The exhibition frames drawing not as a secondary or preparatory act but rather as a primary site of inquiry: “to feel is to think and to think is to feel.” Her watercolour work embodies this by folding emotional states into mark-making that is both delicate and raw.

What I find striking is the emphasis on immediacy. These drawings feel less like polished objects and more like traces of lived experience, materialising what Rosalind Krauss once described as “the index” which is a mark that testifies to presence and process. O’Leary’s practice collapses the distinction between private feeling and public artwork and serves as a reminder that drawing can carry the weight of both intimacy and communication.

This resonates with my own work, in the mix of media choices and the overlap of drawn content and typography, and I connect with O’Leary’s approach to drawing as a mode of translation for complex interior states, particulary those which are negative, traumatic and stressful.

Feeling Drawing Thinking reframes drawing as a thinking tool, but also as an affective one. It encourages me to consider how my own marks (whether stitched, beaded, or painted) might serve as indices of feeling as much as representations of narrative.

Lou Benesch - Untamed Splendor (2023)

Lou Benesch - Untamed Splendor (1) - 2023

Lou Benesch’s 2023 exhibitions Untamed Splendor at Antler Gallery demonstrates the artist’s commitment to reimagining familiar subjects such as animals, plants, and food as symbolic carriers of narrative. Painted in luminous, jewel-toned watercolours, Benesch’s works operate between naturalistic study and allegorical fable. They are not simply depictions of deer, birds, or fruit, but visual devices that suggest myth and collective imagination.

Lou Benesch - Untamed Splendor (2) - 2023

The use of watercolour is significant here. Historically aligned with fragility, domesticity and amateur practice, watercolour has often been considered secondary to oil painting within Western art hierarchies. Benesch’s practice disrupts this narrative and pushes the medium into the realm of the monumental through scale and symbolism. In this way, the work resonates with Glenn Adamson’s assertion in Thinking Through Craft (2007) that so-called “lesser” materials and processes can destabilise established value systems in art.

This has direct relevance to my own MFA practice. Like Benesch, I draw on materials and visual languages that have been culturally coded as “decorative” or “feminine” and explore how they can carry narrative weight. Benesch’s approach reinforces my interest in the symbolic potential of ornament and in the possibility of elevating whimsical or hyper-feminine motifs into vehicles for mythic or cultural storytelling.

Lou Benesch - Untamed Splendor (3) - 2023

What I take from these exhibitions is not only Benesch’s use of imagery, but also her strategic engagement with material histories. By transforming watercolour into a medium of intensity and authority, she demonstrates how artists can reclaim undervalued processes as critical, contemporary strategies.

Lou Benesch - Untamed Splendor (4) - 2023

Cristina Bacchilega - Postmodern Fairy Tales: Gender and Narrative Strategies (1997)

One text that I’ve been reading is Cristina Bacchilega’s Postmodern Fairy Tales: Gender and Narrative Strategies. She talks about how retellings of fairy tales are more than playful updates, they are devices that actively challenge the old structures of power and gender hidden inside the originals. She works to reframe fairytales as cultural tools which shape how we think about gender, power, and morality.

I’ve always been drawn to fairytales and myth, but often through the imagery (enchanted forests, animals, magic). Bacchilega makes me consider how those images are carrying narratives with them, whether I intend it or not. She writes about authors like Angela Carter and Margaret Atwood who twist traditional stories to expose the way women are positioned in them. That feels close to what I want to do visually: to use whimsical or hyper-feminine motifs as a way of reworking the “scripts” we inherit from culture. I’ve been exploring this idea by retelling current events through the visual language of fairytales and medieval imagery, and it feels pertinent - a timeless mode of storytelling, shaped through a feminist lens.

For me the key takeaway is that retelling, whether in words or images, is political. To echo Bacchilega, “Postmodern fairy tales expose the fairy tale’s complicity in cultural processes of gender construction.” In my practice, I want to play with that complicity- leaning into the aesthetic pleasure of fairytales while also twisting them, unsettling their neat morals, and making space for new narratives.

Susan Sontag - An Argument About Beauty (2005)

I’ve been reading Susan Sontag’s 2005 essay “An Argument About Beauty.” What really resonates with me is how conflicted we are about beauty. On one hand, we crave it, surround ourselves with it, and let it shape what we find meaningful. On the other, beauty is often treated as shallow, suspect, or even dangerous. As Sontag puts it, “Beauty has never been democratic. It is always a privilege.” That makes me think about how access to beauty: who gets to embody it, who gets to produce it, has always been tied up with power. It’s also got me thinking about pursuing passion being the realm of the privileged, and also how beauty in architecture and public spaces is typically the realm of the wealthy. These displays of power dynamics are perhaps the most obvious, but nonetheless illustrate the point of the essay well.

Sontag also writes that “beauty defines itself as the antithesis of the ugly,” which makes me think about how rigid those categories can be, and how art has the potential to blur or collapse them. This feels really relevant to my own practice. I’m drawn to things people might dismiss as “pretty” or “girly.” I’ve always felt that pull, but I’ve also felt the cultural baggage that comes with it, like beauty somehow makes the work less serious, and it’s been a hugely limiting belief in my time at RMIT so far. Reading Sontag makes me see that suspicion of beauty as part of a long history, not just my personal hang-up.

What I take from the essay is a reminder that beauty isn’t neutral, but neither is it frivolous. It shapes how we see the world and each other. In my practice, I want to embrace that double edge and to use beauty deliberately, knowing it can seduce and unsettle at the same time.

Barbara Kruger - Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground) - 1989

Barbara Kruger - Untitled (Your body is a battleground), 1989

This week I’ve been looking at Barbara Kruger’s (Untitled) Your Body is a Battleground. It’s such a direct image: a woman’s face cut in half, positive and negative, with the text dropped on top like an advert. But instead of selling us something it’s confronting us with the politics of the body. The message is blunt: our bodies aren’t neutral, they’re sites of power, conflict, and control.

I like how Kruger uses the visual language of graphic design, her bold typography, red blocks and sharp contrasts make her point unavoidable. It feels like design as weapon and communication that refuses to be soft. In a way, it’s the opposite of my practice, where I lean into beads, sparkles, and fairytale imagery, but that’s why I find it exciting. It makes me think about how text and image can collide to amplify meaning, and how “feminine” aesthetics can be just as politically charged as Kruger’s clean, aggressive style.

Kruger’s work also feels timeless, (sadly) the issues of reproductive rights and autonomy she highlighted in 1989 are still relevent now. That makes me reflect on how my own work could carry messages across time, embedding personal and political meaning into materials that might at first glance look whimsical. I’ve been attempting to do this in my studio classes by recreating contemporary events in historical styles, and much to my delight viewers in critique sessions question whether they are looking at something current or historical, so perhaps I am on the right path.

Ella Walker - Various Works

Ella Walker (Untitled), TOAST Magazine, 2020

Looking at Ella Walker’s paintings feels like viewing a historical illuminated frescoe, yet her work feels distinctly contemporary in storytelling and themes. Her figures are flattened and everything seems to exist liminally between history and fantasy. I find myself drawn to the way she treats medieval visual language - she’s developed a set of easily understandable symbols she can remix to tell new stories.

Marina Warner has written about how myths and folktales survive through constant retelling, and I think Walker is doing something similar with images. These works don’t seem to copy medieval forms out of nostalgia; rather they are stitched into contemporary narratives, and this creates a world that is both ancient and current. There’s something feminist about that too, it feels a bit like a reclaiming of a visual history where women’s stories were often marginal.

Ella Walker - Cutting Flowers, 2022, Acrylic dispersion, pigment, chalk, and pencil on canvas, 210 x 100 x 20cm

For me, this resonates with how I approach fairytales, decoration, and narrative storytelling in my own practice. I use a lot of “pretty” motifs, and I’m interested in how those motifs carry cultural weight, suggest the cyclical nature of history, and how they can be recharged with new meaning by using contemporary aesthetics.

Ella Walker - Queen of the Night, 2022, Acrylic dispersion, pigment, chalk, and pencil on canvas, 210 x 120 x 20 cm

Kate Just - Various Works

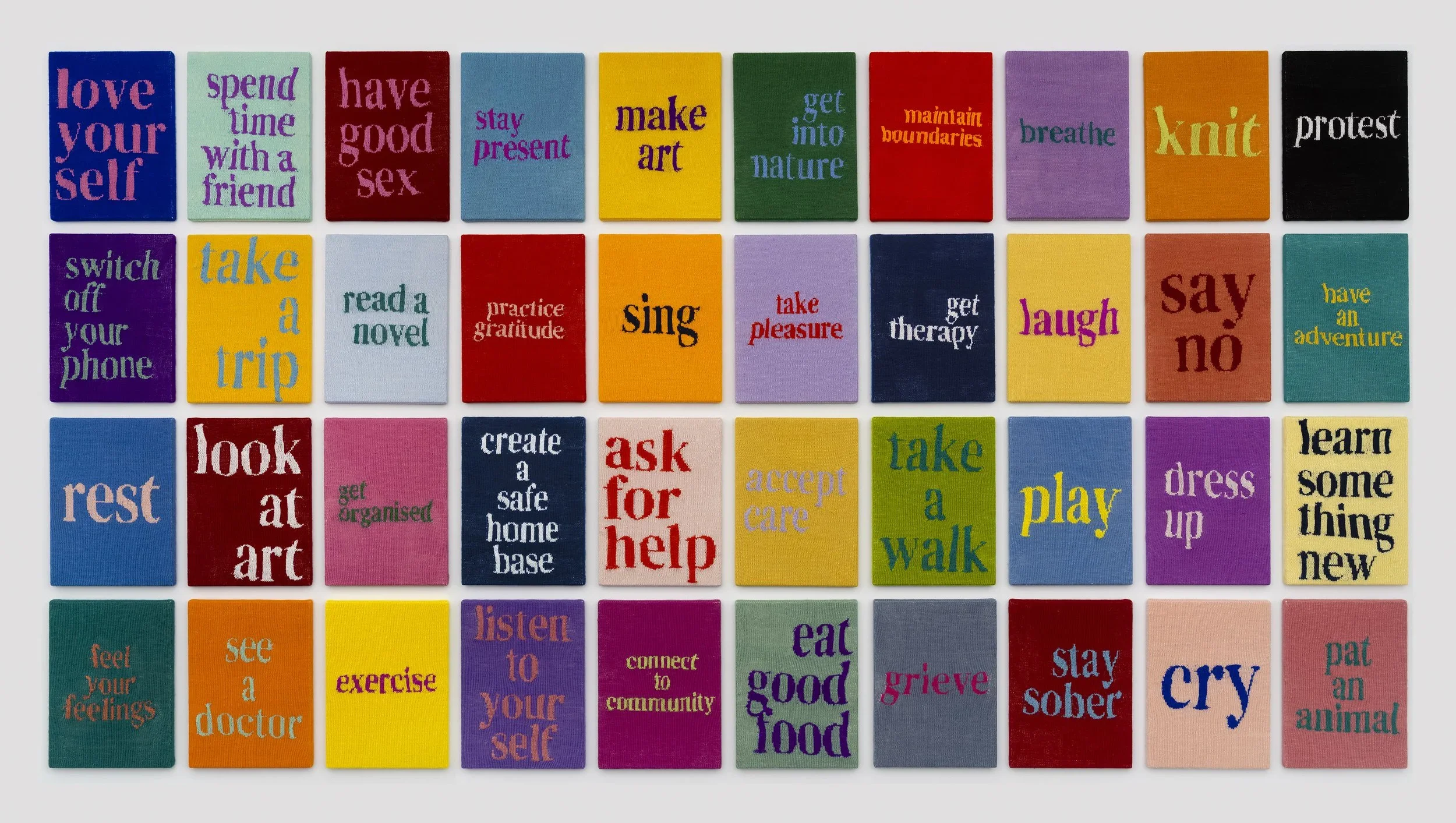

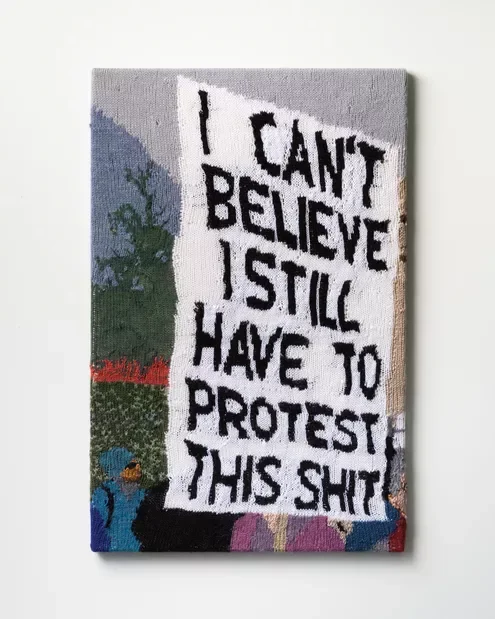

Kate Just - Protest Signs (2022)

This week I’ve been looking at Kate Just’s knitted text works. I deeply resonate with how direct the words are - they are short, sharp statements spelled out in bold typography, but then you realise they’re made through one of the slowest, most patient processes: knitting. The tension between speed of message and slowness of making is what makes them so powerful.

Kate Just - Self Care Action (2022-2023)

I like how this connects to communication design. Just’s pieces still read like posters or banners (direct and didactic) but they’re translated into a material with its own history. Knitting carries associations with care, domesticity, and the feminine, which gives her statements extra weight. It reminds me of what Rozsika Parker called the “subversive stitch”: the way textile practices dismissed as craft or women’s work can become political tools.

For my own practice, where I’m exploring beads, embroidery, and the hyper-feminine as strategies of expression, Just’s work feels like an anchor. She shows how material processes that are coded as “craft” or “feminine” can deliver uncompromisingly direct messages. There’s no apology in it.

Kate Just - Tickled Pink To Be A Woman (2023)

I also like that her work plays with contradiction, soft wool delivering hard truths, slow hands making urgent statements. It makes me think about how my own use of sparkles, fairytale references, and decorative detail can also act as typography in a way and perhaps serve as a clear, visual language that communicates beyond just surface prettiness. As someone who has a background in communication design I’ve often shied away from incorporating typography or obvious hallmarks of comm design in my art practice, however this is showing me there is a world where the two can coexist.

Kate Just - I Can’t Believe I Still Have to Protest this Shit (2021)

Ebony G. Patterson - “...the wailing...guides us home...and there is a bellying on the land...” (2021)

Ebony G. Patterson’s “...the wailing...guides us home...and there is a bellying on the land...” (2021).Credit...Courtesy of the artist and Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago

This week I’ve been looking at Ebony G. Patterson’s immersive garden installations. They’re bright, lush, and glittering - full of beads, sequins, flowers, and patterned fabrics, but there’s always something deeper happening beneath the beauty. Hidden in the layers are figures in grief and references to violence and loss. The work pulls you in with its colour and texture, then slowly reveals heavier, more complex truths.

I’m drawn to how Patterson uses materials and techniques that are often labelled “decorative” or “feminine” (embroidery, beading, sparkles, ornament) and gives them scale and weight. In doing so, she challenges the old hierarchy where craft and beauty were seen as less serious than painting or sculpture. Her work sits within a broader conversation in contemporary art about reclaiming the ornamental as a valid and political form of expression.

In my own practice, I also work with beading, embroidery, and a palette of pinks and purples, often drawing on fairytales and myth. Like Patterson, I’m interested in how something whimsical or hyper-feminine can carry layered meanings about identity, power, and visibility.

Her work has me thinking about scale and atmosphere, and about creating spaces that viewers can step into, so they’re surrounded by the world I’ve built. It’s a reminder that beauty isn’t the opposite of criticality; the two can exist together, feeding off each other to tell a more complete story.

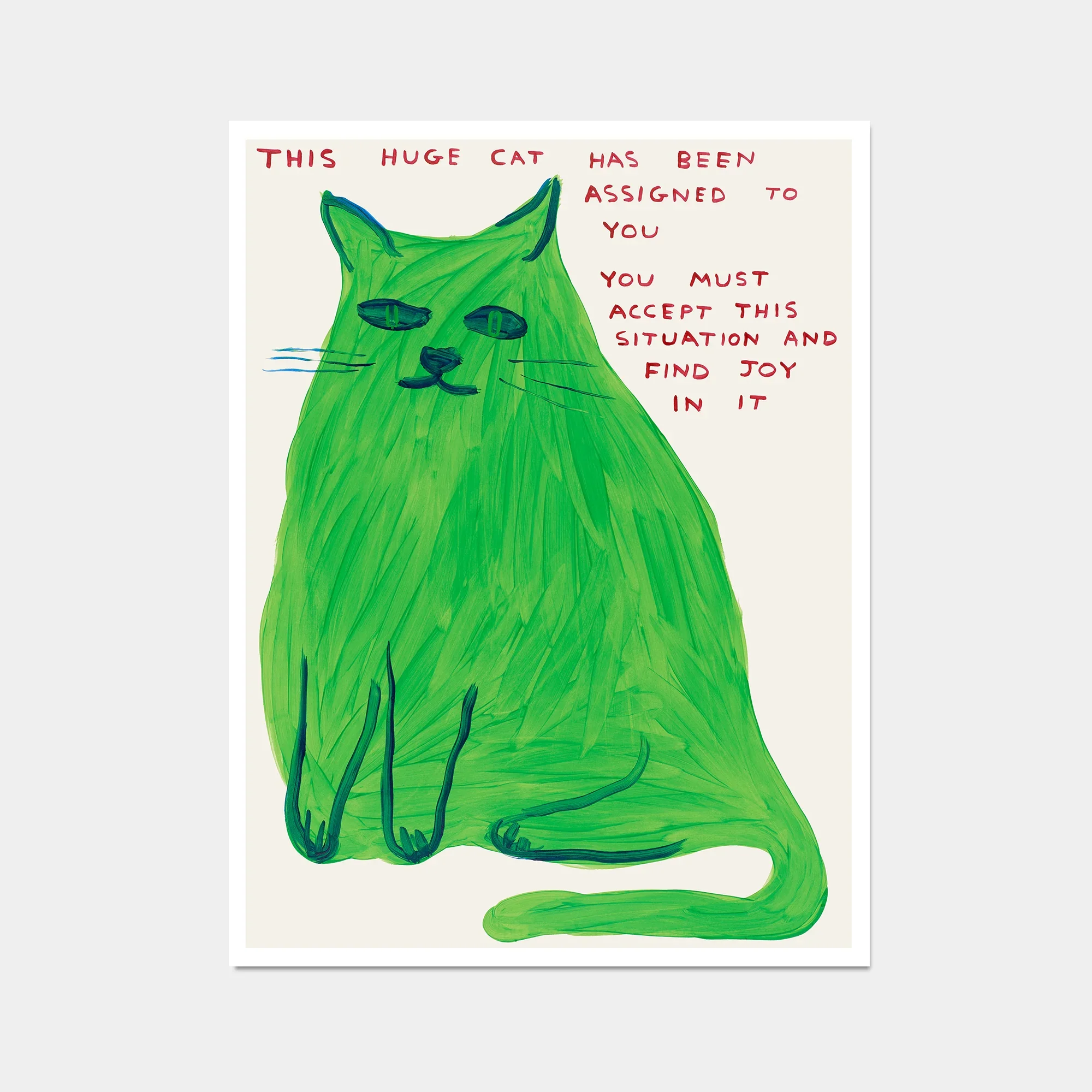

David Shrigley - Untitled (This Huge Cat) - 2022

Irreverent and playful, yet strangely poignant, Untitled (This Huge Cat) speaks to accepting the surprises of life with tenacity and resolve. Although the presence of type from the outset suggests a didactic interpretation, the oddity of the subject matter leads to a questioning of the absurdity of life, and allows for deeper thought and interpretation. Bold shapes and colours come into play here, and the concept is deceptively simple, almost child-like. The playfulness of the work creates an approachability that appeals in a time of social media memes and dwindling attention spans, conveying it’s immediacy and digestibility. The visible brush strokes and loose lines appeal to my aesthetic sensibilities, suggesting a carelessness that contrasts the astute perceptions contained within, but also speaking to the labor and human touch of the artist themselves. Shrigley’s work is determinately human - nothing, from his language to his painting style could be mistaken with the uncanny valley perfection of AI images.

Journal

Random musings, rants, raves, and general chats. Come and hang out with me and listen to me ramble even more than usual!